The next week, Murphy clarified his position:New Jersey's new governor will consider changes to the state's charter school law, potentially slowing the expansion of controversial, yet in-demand schools championed by former Gov. Chris Christie.The state on Friday announced a "comprehensive review" of its charter school law, fulfilling one of Gov. Phil Murphy's campaign promises after an era of rapid school choice growth.

So we need "an objective set of facts," huh? Well, Governor, I've got just the thing with which to start...Gov. Phil Murphy's administration is about to scrutinize charter school law, but that doesn't mean he has it out for charter schools, Murphy said Monday."I have never been nor will I be 'hell no' on charters," the Democratic governor said during a radio appearance on New Jersey 101.5-FM. "I just don't like the way we've done it."[..]"If a school is high performing and kids are doing really well based on an objective set of facts, count me as all in," Murphy said. [emphasis mine]

This week, Julia Sass Rubin, Professor at Rutgers University in the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, and yours truly released a new report: New Jersey Charter Schools: a Data-Driven View, 2018 Update. The report was funded by The Daniel Tanner Foundation, which funded our 2014/2015 series of reports on New Jersey charter schools.

If the reaction to this latest report is anything like the reaction to the previous series, you're probably going to see some serious pushback to our work over the next few weeks. So I want to spend the next few posts here going over exactly what Julia and I did in this report, and why we both believe Governor Murphy is correct in wanting to give serious thought to overhauling New Jersey's charter school laws and regulations.

But let me start with an overview:

- New Jersey charter schools are transferred a lot of money away from the public district schools.

This graph didn't make it into the final report, but it's still instructive. Year after year, charter schools are taking a larger share of the state's total school funding. This is highly problematic, as charter schools create redundant systems of school administration. Yet the state has not bothered to take a serious look at what this means for the overall fiscal health of NJ's public school system.

- The effects of charter proliferation in New Jersey are much more widespread than commonly reported.

The discussions around New Jersey charter schools mostly focus on their impacts in places like Newark and Camden. Unquestionably, these are the communities that feel the effects of charter schools growth the most -- but they aren't the only ones. There are charter schools in New Jersey that draw from over 40 different districts, which means the fiscal effects of charter growth are felt in public school districts all over the state.

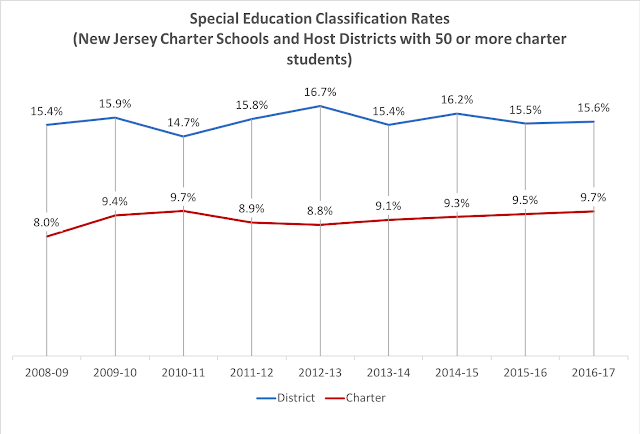

- NJ charter schools do not enroll as many students with special education needs as public, district schools.

- The effects of charter proliferation in New Jersey are much more widespread than commonly reported.

The discussions around New Jersey charter schools mostly focus on their impacts in places like Newark and Camden. Unquestionably, these are the communities that feel the effects of charter schools growth the most -- but they aren't the only ones. There are charter schools in New Jersey that draw from over 40 different districts, which means the fiscal effects of charter growth are felt in public school districts all over the state.

- NJ charter schools do not enroll as many students with special education needs as public, district schools.

This data actually mirrors similar data presented by the New Jersey Charter School Association. It's a simple fact: the students in the charters are much less likely to be classified as having a learning disability compared to those in the public district schools. It amazes me that anyone would try to argue this point.

- NJ charter schools do not enroll as many students who are Limited English Proficient (LEP) as public, district schools.

Again, it's pointless to argue about this. This is the state's own data, and the pattern is very clear.

- There is wide variation in the differences in student socio-economic status between NJ's charter and district schools.

There are communities where the charter student population has close to the same proportion of free lunch-eligible students as the public school district. But there are many places where the charter population is very different compared to the district school population. In some places, the charters enroll many more FL students; in some places, the charters enroll far fewer FL students. Both of these situations are cause for concern.

It's also worth noting that free lunch-eligibility may be increasingly unreliable of a measure of student socio-economic status. If we care about the segregative effects of charter schools, we need to start collecting better data.

Again, I'll get into these individual points over the next few posts. But let me conclude this introductory post with this thought:

In New Jersey, a local community has no say in whether it has to pay for resident students to attend charter schools. This includes many towns where charters are not located. If a resident family in your school district wants their child to attend a charter miles away in a town that isn't close to yours, your town's taxpayers must still come up with the money to subsidize that "choice."

In other words: The power to approve, regulate, and expand charter schools is not aligned with the fiscal burdens of paying for those charters. This is a serious problem that must be addressed in any future legislative overhaul.

Much more to come -- stand by...

- There is wide variation in the differences in student socio-economic status between NJ's charter and district schools.

There are communities where the charter student population has close to the same proportion of free lunch-eligible students as the public school district. But there are many places where the charter population is very different compared to the district school population. In some places, the charters enroll many more FL students; in some places, the charters enroll far fewer FL students. Both of these situations are cause for concern.

It's also worth noting that free lunch-eligibility may be increasingly unreliable of a measure of student socio-economic status. If we care about the segregative effects of charter schools, we need to start collecting better data.

Again, I'll get into these individual points over the next few posts. But let me conclude this introductory post with this thought:

In New Jersey, a local community has no say in whether it has to pay for resident students to attend charter schools. This includes many towns where charters are not located. If a resident family in your school district wants their child to attend a charter miles away in a town that isn't close to yours, your town's taxpayers must still come up with the money to subsidize that "choice."

In other words: The power to approve, regulate, and expand charter schools is not aligned with the fiscal burdens of paying for those charters. This is a serious problem that must be addressed in any future legislative overhaul.

Much more to come -- stand by...

No comments:

Post a Comment