Among the consequences is an almost certain change in how charter schools are approved and renewed. Although Murphy's stance on charters is "complicated," he is clearly far more skeptical than Chris Christie. And now that Shiela Oliver has joined the ticket, it's even more likely charter schools will have to clear a much higher bar when seeking approval from the state.

Which means that for the next few months, the state's charter sector is getting while the getting is good:

So, who's getting the nod in this latest round of charter growth?When Gov. Chris Christie leaves office in six months, one of his clear legacies will be the growth of charter schools in New Jersey, with school enrollment more than doubling in his eight years in office.Yesterday, his administration finished the job, announcing the final approval of five more schools to open this fall. That brings to 89 the number of charters that will be open when Christie steps down in January.That number isn’t that big an increase from the 70 in place in 2010 at the start of Christie’s tenure, a number that jumped to over 90 in his first year. But his administration ultimately closed nearly 20 charter schools as well.Nevertheless, there will be close to 50,000 students enrolled in charters this fall, according to the state, up from less than 25,000 when he took office. More than 56,000 seats will be authorized with the latest approvals.

Three "Achieve" charter schools? Not quite: Achieve Community is aligned with the team behind Brick/Avon Academy in Newark (one of the main subjects of Dale Russakoff's The Prize). But the two College Achieve charters are both being founded by a fellow named Michael Piscal.The five new schools announced yesterday to open in the fall were:

And that brings us to an interesting story that sheds a bright light on the New Jersey charter school approval process, and why it really needs to change...

Because Piscal already has a charter school in New Jersey: College Achieve Central Charter School in Plainfield. Fiscal founded the school after a career in school management in California -- a career Darcie Cimarusti, aka Mother Crusader, detailed in 2014:

In the very same month Pallas wrote this piece it became very clear that not only were ICEF schools not the miracles they were portrayed to be, there were very real problems at ICEF that threatened their very existence. The downward spiral was chronicled by Los Angeles Times writer Howard Blume.Read the whole thing, as they say. The point here is that, according to Cimarusti's research, Piscal's previous charter network had expanded too quickly, putting it in a financially untenable position. That's why David Rutherford, a member of the Plainfield Board of Education, argued back in 2015 that giving a charter approval to someone with Piscal's history was a real risk:

A group of the city's leading philanthropists, including billionaire Eli Broad and former mayor Richard Riordan, rallied Monday to save ICEF Public Schools, one of the nation's largest and most successful charter school companies, which was teetering on financial insolvency.ICEF, which operates 15 schools in low-income minority neighborhoods of Los Angeles, was virtually out of cash, unlikely to meet its Oct. 1 payroll. The nonprofit faced a $2-million deficit in the current budget year as well as substantial long-term debt.The collapse of ICEF would have been a blow to the charter movement and to the 4,500 students and several hundred employees of an organization whose results have impressed many observers. Charters are independently run public schools that are free from many regulations that govern traditional schools.ICEF representatives and others said the group's budget problems were caused by insufficient reserves; an overly ambitious expansion — 11 new schools in three years — that resulted in costly debt; and a reluctance to make cuts affecting students. These factors were exacerbated by the recession, which sharply reduced state funding to schools, and this year's late state budget, which has delayed payments to schools.The rescue plan that emerged Monday was less disruptive than one under discussion as recently as Sunday. That plan would have broken up ICEF, distributed schools and students among other charter schools and forced out founder Mike Piscal.Instead, Piscal will remain to oversee academic programs.(emphasis mine)Well, so much for Piscal's theory that ICEF was infallible.

Let me add a little more context with the benefit of hindsight:As reported in the Los Angeles Times, ICEF leaders took pride in their “secret sauce”, a balanced program of “academics and extracurricular activities.” According to some parents, the more troubling secrets at the ICEF were the day to day behavior of its enigmatic leadership.In the words of former Los Angeles United School District Board of Education President Caprise Young, ICEF exhibited “substantial bad judgement and lack of transparency with [its] finances,” which lead Piscal’s organization to a financial near-death experience in 2010. This is all despite cutting corners.Apparently, employees complained of supply shortages, and were worked long hours with no additional compensation. It’s no suprise that teacher turnover ranged from 10 to 50 percent each year in ICEF’s schools, which served 4,500 students.An even larger corporate charter school outfit, Alliance, wished to purchase the struggling company, but the sale fell though. It was ultimately new investors and uber-rich donors sympathetic to the charter school movement that prevented the total dissolution of the Inner City Educational Foundation.As for ICEF’s founder, Mike Pascal, he had to go. According to the Los Angeles Times, Piscal resigned amidst the controversy in October of 2010. Los Angeles social justice writer and education advocate Robert D. Skeels, who followed the situation closely, asked in early 2011 “Where’s the money, Mike?” concluding that even if there was no criminal malfeasance, Piscal would have committed “the most unconscionably incompetent accounting of all time”. [emphasis mine]

In 2013, Camden Community Charter School opened under the aegis of the NJDOE, even though the school's founders were, at the time, under investigation by the Pennsylvania State Auditor General. You might have thought NJDOE would show some restraint and wait until the investigation was closed before allowing CCCS to open its doors; alas, no. Guess what?

The NJDOE ordered it closed in the spring of 2017. Sue Altman has all the gory details, noting that NJDOE was not solely to blame, as backing CCCS was a bipartisan effort. Still, NJDOE is supposed to be the backstop; it's supposed to look carefully at the charter applications and determine, based on whatever evidence may exist of the founders' pasts, the chances of that charter succeeding.

Which begs the question: did NJDOE do proper due diligence on the new College Achieve charter approvals? Specifically, did the department look carefully at CACCS's record in Plainfield -- short though it may be -- and make an informed decision about how the expansion of the charter chain will affect Paterson, Asbury Park, and Neptune, its sending districts?

I'll bet you know the answer. And I'll bet you know by now I just can't resist a chance to take a data dive:

We'll start with the percentage of free-lunch eligible students in the charter and its hosting district. Plainfield has a large proportion of student in economic disadvantage. But CACCS's free lunch percentage actually decreased over the last two years.

Plainfield also has a large number of Limited English Proficient students (due to its large population of Spanish-speaking residents). CACCS's LEP percentage did go up last year, but, like almost every other charter in the state, it's still far behind its hosting district schools.

That goes for special education students as well: Plainfield City Public Schools has more than three times the proportion of classified students as College Achieve Central Charter School. Again, this is quite typical for the state's charter sector.

CACCS has a track record of serving a fundamentally different student population than the Plainfield public schools. Did NJDOE take this into account when approving their expansion into the other towns?

State statute requires: "The admission policy of the charter school shall, to the maximum extent practicable, seek the enrollment of a cross section of the community's school age population including racial and academic factors." The outcomes suggest CACCS has some work to do on this front. Did NJDOE require a plan from the applicants to address this issue, either in Plainfield or in the new locations?

And did NJDOE take into account the fiscal impact on Asbury Park, Neptune, and Paterson from the new charters? Let's look at the spending of CACCS compared to the PCPS:

Again, CACCS follows a pattern I've documented across the state: lower overall budgetary per pupil costs, but driven by less spending "in the classroom." I don't have good staff data for CACCS, but if they're like almost all other charters in the state, their teachers are likely less experienced and, therefore, less expensive than PCPS teachers. This creates a "free riding" problem for the area public schools, where CACCS gets the benefits of PCPS's higher salaries for more experienced teachers.

Another big factor here is how much less CACCS spends per pupil on support services: the services which largely benefit special needs students, like child study teams, nurses, physical and metal health services, etc. Of course, CACCS doesn't need to spend as much as PCPS, because their student population has a much smaller proportion of students who need those services.

Again: did NJDOE take this into account when giving the OK to College Achieve in their new districts? How does NJDOE expect Asbury Park's, Neptune's, and Paterson's public schools -- and, for that matter, Plainfield's -- to absorb the cost of concentrating more special needs students into their districts?

Notice also that CACCS spends much more per pupil than PCPS on administrative costs. Let's zoom in on that:

CACCS spends less than PCPS on instruction and support, but much more on administrative costs, including salaries. As Bruce Baker spells out, charters are generally too small to reach an optimal size for fiscal efficiency. High administrative spending isn't necessarily indicative of anything nefarious -- it's just a logical consequence of establishing inefficiently small schools that essentially operate as their own school districts.

Again, NJDOE had a clear example from CACCS that they can't, as of yet, lower their administrative costs to stay in line with the local public school district, even with a smaller proportion of costlier special needs students. Maybe CACCS will get better -- but why not, then, wait until they prove they can operate more efficiently? Why not wait until they've established their track record in Plainfield before allowing them to expand?

Especially when their outcomes aren't really that much better?

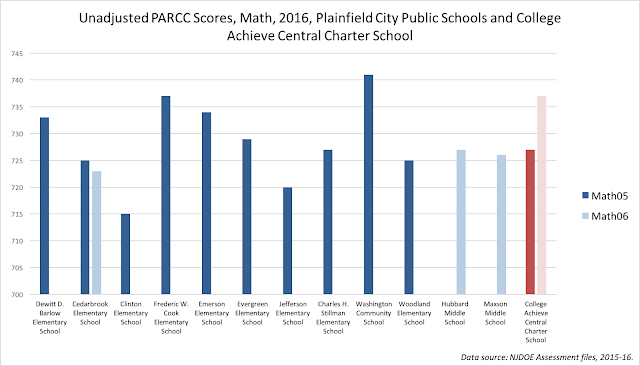

Here are the PARCC mean scale scores in English Language Arts from 2016 for Plainfield City Public Schools and CACCS. In Grade 5, CACCS is quite average: higher scores than some schools, lower than others. They do somewhat better in Grade 6, but only beat PCPS's lowest scoring school by five points on a test whose score ranges from 650 to 850.

Even NJDOE acknowledges this, which is why they calculate Student Growth Percentiles (SGPs) for every school enrolling students in grades 3 through 8. There are significant problems with SGPs (I know I keep promising I'll have more to say about this -- later this summer, I promise...), but NJDOE has said themselves they are necessary because schools serving higher numbers of lower-performing students can still show "growth," and that should be acknowledged.

So how are CACCS's growth scores?

By any normal standard, CACCS is quite average in its ELA growth scores compared to the PCPS -- some might say even a little below average, although given the statistical noise in these measures I wouldn't go that far.

Again, math growth is not superior compared to PCPS; it's quite typical.

I've used my own "value-added" model before when evaluating charter school performance*, which adjusts mean scale scores based on demographic comparisons across the state. Here are the adjusted outcomes:

I am not one to ever make the case that a school's effectiveness should be solely measured by its test score outcomes, no matter how we calculate them. But if NJDOE is granting an expansion for College Achieve into new school districts, we ought to ask: why? What are they seeing that the data does not show? Because the data is clear:

Compared to the Plainfield Public Schools, College Achieve Central Charter School enrolls proportionally fewer free lunch-eligible, Limited English Proficient, and special education students; spends much less on instruction and support and much more on administration; and does not get test score outcomes that are superior.

So, based on the record in Plainfield, what benefit is there to Paterson's, Asbury Park's, or Neptune's families in allowing College Achieve to set up shop in these communities? More importantly: is that benefit worth the cost to these communities?

Will College Achieve pick up the slack here? Will it be able, with its high administrative costs, to establish a similar institute, and provide all the other programming Asbury Park provides to all of the district's students? And do the same for Neptune and Paterson?Board administrator Geoffrey Hastings said a total of $3,266,750 was cut from the Asbury Park School District budget and redirected to the College Achieve. This resulted in layoffs and the need to eliminate jobs. Some of the staff were rehired through attrition but others turned in their resignations and retirement notices, Hastings said.Among them was Brian Stokes, who headed the College and Career Readiness Institute, known for transforming students’ focus on their future by administering workshops, panels with nationally recognized professionals and paid internships with city and area businesses. [emphasis mine]

Again: NJDOE has approved charter schools with extensive out-of-state records that would suggest caution at the least. In the case of Camden Community Charter School, it turns out they should have looked at that record more carefully. Now comes College Achievement, looking to expand rapidly across the state.

Maybe Piscal was able to convince charter authorizers that his dubious past in Los Angeles was behind him, and that he had a solid plan for success in Plainfield. OK... But why, then, rush to allow expansion to other communities when we're just starting to get a picture of how College Achieve's first campus is faring? Why allow College Achieve to expand when it's student populations are different, when it's administrative expenses are high, and when it's outcomes aren't at all superior?

I have no doubt that CACCS has many dedicated educators committed to their students. I am sure the school is full of bright, hard-working students with supportive parents who should be proud of their hard work and achievements. But when a charter school comes into a community, it affects all students. NJDOE has an obligation to look carefully at what those effects may be.

There was no need to rush through College Achieve's expansion. Let's see what they can do in Plainfield first, and then let the citizens of Asbury Park, Neptune, and Paterson decide, openly and democratically, whether any potential benefits from this charter chain's proliferation is worth the costs.

h/t Rob Tornoe

ADDING: One additional point, based on a rather fawning article from mycentraljersey.com:

On Monday, a year after opening its first school in Plainfield, CAPS is opening its latest venture — the College Achieve Central Charter School (CACCS). The first charter school for the borough, and only the third in Somerset County, CACCS, will educate students with an instructional program that emphasizes writing and history as well as a challenging science, technology, engineering, math and arts (STEAM) curriculum.

[...]

The new facility at 107 Westervelt Ave. is being financed and developed by Building Hope, a nonprofit organization that has provided more than $200 million in facility funds to academically successful schools, so they can expand and grow their enrollments. College Achieve is the first facility in New Jersey to be developed by Building Hope. The school will lease the campus from Building Hope with plans to eventually purchase it. [emphasis mine]Long time readers may remember my series of pieces, back from 2013, about Building Hope. The outfit basically gathers government and private foundation money (The Walton family is a big contributor), then gives out loans for charter construction at below-market rates. It's a good deal for the foundations because the loans are paid back, and the foundations get to count "imputed interest" as charitable giving without seeing their coffers actually diminish.

There are at least two points to be made here. First: the taxpayers of Plainfield, North Plainfield, and New Jersey overall are paying money to College Achieve, which is being used to purchase a building the taxpayers do not own. State tax records show Building Hope owns the building -- not the state, and not the local school district.

When College Achieve says they have "plans to eventually purchase it," what do they mean? That it will be owned by a private entity? A nonprofit or a for-profit? A group or an individual? Who determines the rental rates College Achieve currently pays? What will happen to those funds if they buy the building and the debt is retired? Will someone be paid to administer the property if it's sold? Who? How much?

As Bruce Baker and Gary Miron document in great detail, our current chartering system is set up so that taxpayer funds are used to purchase assets the taxpayers themselves do not own. This makes no sense.

I hope Piscal's New Jersey charters don't suffer the fate his Los Angeles charters did, because I very much doubt there will be a couple of white knights around this time to ride in and rescue them. But if they do, who will own the assets New Jersey taxpayers have paid for?

Second: time and again I hear from our state's charter cheerleaders that the sector is disadvantaged because it has to raise funds to finance its own facilities. Can we please stop with that?

Building Hope operates with a great deal of governmental largesse, and the foundations it relies on exist only because the tax code allows it. Further, over and over and over and over and over and over again we find that charter schools have access to all sorts of capital and financing that public district schools do not. Again, much of this financing is made available because the tax code provides incentives; by any standard, that is publicly-subsidized financing.

* One important point about these adjusted scores compared to models I've used before: I don't have school-level special education data for CACCS that is comparable to PCPS data. What I present above is district level data, which isn't what's needed for this model.

That said, I did take a look at the school-level special eduction rates for the three middle schools in PCPS for 2013-14. They are high: between 14 and 22 percent. I have little doubt the "value-added" would grow considerably for the PCPS middle schools if I were able to include this as a covariate.

As always: caveat regressor.