Bennett's excuses would even make Anthony Weiner wince:

Bennett says his department ran into problems when initial calculations indicated the school would receive a C under the statewide accountability system, which didn’t sit well with the then-superintendent.

“So when we looked at our data and saw that three of those schools were A’s and Christel House was not, that told me that there was a nuance in our data,” says Bennett. “Frankly, my emails portrayed correctly my frustrations with the fact that there was a nuance in the system that did not lend itself to face validity.” [emphasis mine]Read the emails and judge for yourself; personally, I read Bennett's frustration arising from the fact that he made himself look like a fool after running around Indiana praising Christel House Academy, the charter in question.

You can certainly understand the fury of local school officials around Indiana after learning of Bennett's perfidy. "Why," they must wonder, "was Christel House given the benefit of the doubt?" It's a fair question: what made this charter so special (other than the $90,000 Christel Deehan donated to Bennett's failed re-elction bid)? The backbone of the case for the charter is that it was "beating the odds": it had just as many poor students as the public schools of Indianapolis, but was getting far better results.

Give Christel House credit: they've never shied away from taking poor kids (click to enlarge):

On the other hand:

Christel House is a laggard when it comes to serving special needs students. That may be because the school has a "voluntary" essay question in its application form that asks parents to: "Please describe the academic and social goals you have for your child's growth and development for the coming school year." Not exactly welcoming to the reluctant special education parent.

Keep all this in mind as we look at Christel House's test performance.

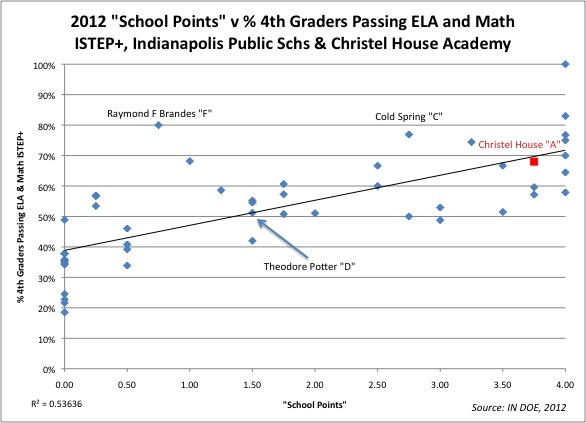

Each data point here is either an IPS school that reported scores for 4th Grade, or Christel House, which is marked in red. The x-axis is the grade the school received from the IN-DOE in "school points"; depending on the cutoff points, the number of school points determines the letter grade for a school. The y-axis shows the percentage of all students at the school who passed both the language arts and math exams in 2012.

You'll notice the r-squared number in the bottom left; this is geek-speak, saying that about 73% of the "school points" grade can be explained by the schools' passing rates. We'll talk about this more in a bit, but for now: this is a fairly strong correlation. As Matt DiCarlo explains in a post about Indiana's school grading system, the school grade is based on "growth" - how much students improve - as well as "absolute" performance. So we don't expect the school points to match the passing rates exactly, but they do track relatively closely.

I've also mapped out a few other schools for comparison, but here's the thing: it's difficult to measure these schools against each other because they don't serve the same grades as Christel House. Bennett even bases his excuse on this discrepancy:

At issue were the school’s low scores on statewide algebra tests. Bennett says the problem stemmed from how combined schools— that is, those that include multiple grade levels — are counted under the state’s accountability system. He says the tweaks his department made benefited a number of schools, not just Christel House, which is run by a prominent Republican donor.Well, if that's true, then by all rights Indianapolis's elementary schools should not be judged against the performance of Christel House's middle school students. It only makes sense: why should an elementary school be made to look bad in comparison to Christel House if they aren't even teaching the same grades?

Let's pull out a few individual grade levels, then, and see how the IPS public schools compare to the charter founded by Bennett's patron. Here's sixth grade (in Indianapolis, most elementary schools go through sixth grade):

Well, things have shifted a little, but it still looks like Christel House tops the lower-graded schools. How about fifth grade?

OK, wait a minute; what's going on here? Theodore Potter School, which earned a 'D' for its school grade, has more kids passing the Grade 5 state test than Christel House! And the others aren't too far behind. What about Grade 4?

Here's a surprise: a "C" school and an "F" school did better than Christel House on the fourth grade state tests, but Christel House won the "A"! 77% of Cold Spring's 4th Graders passed the tests; 80% of the fourth grade at Raymond F. Brandes School also passed. Yet neither got Christel House's "A," even though only 68% of their fourth grade passed. Let's look at Grade 3:

Well, good for Christel House this time. But you have to wonder about the wide swings in the other schools. Was 2012's fourth grade cohort at Brandes really that much superior to 2012's third grade? And what does it say that the 60 point gap in third grade between Brandes and Christel House is reduced to 27 points in sixth grade? Isn't that a good thing (even if we are talking about different cohorts of students)?

In any case: when comparing these schools to Christel House, remember that most of them do not teach seventh or eight grade. That gives Christel an advantage:

Relative to other middle schools Christel is good; not a miracle worker, but very solid. It appears, however, that their high middle school scores were used to give them a boost to "A"-status, even as they fell behind lower-graded elementary schools in some of the lower grades. It seems obvious: the Indiana DOE, under Tony Bennett, gave an advantage to this combined school that made their elementary test results look superior to the schools with only younger students.

"Hold on!" I hear some of you cry. "Isn't that what we actually want? Don't we want more students passing in the higher grades? Isn't that proof that Christel House's students are 'catching up' from their slow starts?"

Would that it were true:

Here are the passing rates for each cohort of students who "graduate" in eight grade from Christel House; I've only included those for which the IN-DOE had three or more years of test scores. These are the combined pass rates for math and language arts, just like above. There is no pattern of "catching up": the passing rates bounce up and down for each class. We can't be sure what going on here: is this is a phenomenon arising from the shifting difficultly of the tests from year-to-year? The shifting criteria for a passing grade? Cohort effects? (All these, by the way, add up to yet another reason to avoid mandating high-stakes decisions based on tests.)

In any case, there's not much evidence here that Christel House's students "catch up" more than students in the IPS district's schools (if someone wants to look at Christel's rate changes for each cohort against other schools, be my guest). What we see instead is that Christel House was able to take advantage of a change in the rules of the game - a change that got them an "A," even though other schools that got poor grades had better passing rates in various grade levels.

But let's put aside Bennett's contortions for a moment and think a little more about the relationship between each school's performance and its grade. Here, once again, is the relationship between school points, which determine the grade, and a school's passing rate for all students:

We've been looking a small sample of Indiana's total number of schools - just Christel and the IPS schools - and the FRPL rates are fairly close. But if we were broaden this out to include the entire state, we'd see that poverty rates correlate strongly to passing rates. And that, explains DiCarlo, puts the schools serving poor kids at a distinct disadvantage:

You can see this in the scatterplot below, which presents passing rates (in reading only) by school poverty, with the red horizontal line representing the 70 percent cutoff. Almost none of the schools below the line have free/reduced-price lunch rates lower than 50 percent.

On the flip side of this coin, the schools with rates above 70 percent (above the red line), some of which are higher-poverty schools, have no risk of a failing final grade, even if they receive the lowest possible growth scores. A grade of D is the floor for them.

So, it’s true that even the schools with the lowest pass rates have a shot at a C, so long as they get the maximum net growth adjustment, and also that the schools with the highest passing rates might very well get a lackluster final grade (a C, if they tank on the growth component).However, the most significant grades in any accountability system are at the extremes (in this case, A and F), as these are the ratings to which policy consequences (or rewards) are usually attached.

Not only that: as Bruce Baker has pointed out, there appears to be a relationship between test score "growth" and "performance"at the school level: the higher you start out, the more you "grow." I really don't know how New Jersey's growth model compares to Indiana's, but at first glance the basic construction seems similar: a "student growth percentile" with no covariates for student characteristics.And, under Indiana’s system, a huge chunk of schools, most of which serve advantaged student populations, literally face no risk of getting an F, while almost one in five schools, virtually every one of which with a relatively high poverty rate, has no shot at an A grade, no matter how effective they might be. And, to reiterate, this is a feature of the system, not a bug – any rating scheme that relies heavily on absolute performance will generate ratings that are strongly associated with student characteristics like poverty. It’s just a matter of degree. [emphasis mine]

So let's see where the public schools of Indianapolis, serving many children in poverty, stand when it comes to their school grades:

- They have to compete against schools that don't teach the same grade levels, which creates a bias against them.

- Because of poverty, they start out with lower "absolute" scores, which decreases their chance of showing "growth" in the IN-DOE's model.

- Even if they do show growth, the A-F system is designed to keep them from earning the highest grades, while affluent, high-performing schools can't get the lowest grades.

- The system has so little transparency and accountability that the commissioner can change the rules in the middle of the game.

As I said before: Tony Bennett needs to resign. But even more importantly, this entire A-F system needs to be overhauled, if not thrown away. Just the fact that a group of schools' relative passing rates can vary so much from grade to grade is enough for us to give pause when rating the performance of an entire school. Add to that the bias against schools with high poverty concentrations, the gaming of the system to favor combined-level schools (most of which are probably charters), and the near-impossible hurdles in "growth" that poor schools face...

You wouldn't even need a guy like Tony Bennett at the helm for this thing to run aground (although it helps...).

Changing grades, that is...

ADDING: Reading the emails, it's interesting that the IN-DOE staff views Grades 3 through 8 as a unit, and high school as another unit. There's no evidence that the staff understands it's possible that judging a K-6 school and a K-8 school may yield a false comparison.

3 comments:

Does this school actually serve poor students in numbers proportionate to real public schools?

It's a long-standing practice of charter schools to make that claim, but when you tease out the numbers, you usually find that they don't enroll as many students receiving free lunch, a marker for deeper poverty. It's always "free-and reduced lunch" that they deceptively hide behind.

Personally, based on their longstanding behavior, I don't believe a word they say, ever.

They change grades, they change criteria, THEY DO WHATEVER THEY WANT. When Newark met QSAC's expectation of a grade B, they turned around and made the stakes higher and then changed the grade to a C. No you can't have your district we want the money.

Michael, you are, of course, correct. I didn't want to get into that - this post is already too long as it is! - but Christel Houses's Free Lunch numbers actually stack up pretty well compared to the public schools.

I was going to include all charter schools in Indianapolis here, but there's a glitch: there's no good way to tease them out of the rest of the county, which uses "Indianapolis" as the mailing city even when they aren't in the city limits.

A full analysis is a big project, and I've got a garage to clean out...

As always, thanks for reading.

Post a Comment