If you follow me on Twitter, you probably noticed a few comments about a new report I have out with the Fordham Institute:

Robbers or Victims? Charter Schools and District Finances. I'm putting my thoughts here so you know they are mine and mine alone. Hopefully, I can shed light on what the report finds and what I believe that means.

Let me start by saying I don't think a have a false sense of my place in the ongoing debate about education policy: I'm a teacher and blogger who went and got a PhD in the field, who continues to teach K12 (but also teaches grad students in education policy part-time), and has a bit of following on social media (although not nearly as large as others). My blog is full of posts that call out what I believe is bad research in support of education "reform" -- especially charter schools. I also put out reports now and then for a variety of groups that have cast doubt on charter school "success" stories.

Given this, it was a surprise to me when I got an email last year from Fordham, asking about a

working paper based on my dissertation. Fordham is well known as a supporter of charter schools, and regularly produces research supporting their expansion. Why would they want to work with me? Did they know who I am and what I've done?

It turns out they did. They were considering doing a study very similar to what I had done in my dissertation, assessing the impact of charter school growth on the finances of "hosting" public school districts. In other words: what happens to district finances when charter schools start proliferating within a district's boundaries?

What I had found – and what I still found in this latest report – is that as charter schools grow, per pupil spending in school districts increases. This is in contradiction to what some charter critics have suggested: that spending in host districts schools goes down as charters grow. To be honest, it was contrary to what I thought I was going to find,,, until I started digging further into the data.

I'll go into that in a minute; first, let me explain why I took the gig.

Working With Fordham

We are obviously in a time of intense polarization along ideological lines -- and that includes education policy. For myself, I draw a distinction between those who I think are arguing in good faith, and those who aren't. I'll admit it's not always a bright, clear line; however, I am trying to be open to the possibility that people can disagree on things like charter schools but still have meaningful and productive dialogue.

Before I agreed to working on the report, I did take a second look at Fordham's body of work. Some I think is just wrong -- not so much in its methods as in the conclusions they come to based on their findings. But some I think is valid and worthwhile. I disagree with Fordham's president, Michael Petrilli, about any numbers of questions around education policy. But I also acknowledge he's been one of the few charter school supporters who's willing to concede that "no excuses" charters do not enroll similar populations as public district schools (a point I find so obvious that I don't believe I can have a good faith discussion with anyone who doesn't agree).

I also knew that if I turned down the gig, someone else would do it, and I wouldn't get a chance to further my work in this field. Yes, I got paid... but it's hardly a fortune, especially considering the amount of time I've put in (and I understand my fee was substantially less than many other better-known researchers who have written reports for them).

There was always the agreement that there would be an introduction that would not be under my name. So long as everything else met my approval, I thought that was fair. I suppose I could have asked for a "rebuttal," but I didn't want it subjected to their editorial review; hence, this post.

Let me say one other thing that readers can take or leave depending on whether they want to trust my word: this was one of the most rigorous review processes I've been involved with. That's not to say the work couldn't be improved; as I say below, rereading after getting reactions this week, I do wish we had made some revisions.

But I was allowed to suggest my own reviewers, and considered myself lucky to have two of the best researchers working in this field, Paul Bruno and Charisse Gulosino, agree. David Griffith at Fordham was also quite demanding, and insisted on having me spell out in great detail nearly every decision I made in creating both the dataset and the models.

Again: this report is hardly the last word on whether and how charter school growth affects school district finances. There are several very big limitations on what I found, and the approach I took does not at all lead us to a definitive answer as to whether charter growth is helpful, harmful, or neutral to district finances. That said, I hope, at the very least, the report helps frame the question in a way that is useful. Because, until now, I don't think many charter supporters (like Fordham) or skeptics (like myself) have been viewing the problem the right way.

Fixed Costs and Charter School Growth

Let's set up an example with numbers that are easy to work with. Imagine a school district with 5,000 students in 10 schools, each with 500 students. Each of those schools has 20 classes of 25 students each. That means 20 classroom teachers –– but it also means one principal, one librarian, one guidance counselor, one nurse, etc.

The salaries and benefits paid to the classroom teachers in this example are instructional spending: spending that goes directly to the instruction of students. The principal, librarian, counselor, etc. salaries are support spending: spending that is for the support of students but not directly related to instruction. This is an important distinction to keep in mind.

Next, a charter school comes to town and begins drawing students away from the district. Let's say it takes away five percent of the enrollment, or one classroom's worth of kids.

We'll assume this happens across the district: every school loses 25 students to the charter.

What happens across the district? Well, each school now has the equivalent of 19 classrooms, not 20. To maintain the same instructional cost per pupil, the district will have to let one teacher go at each school. This might be through retirement and hiring freezes, or through outright firing of teachers. Obviously, the district will have the ability to shuffle teachers around as needed between buildings, so the teacher reductions can play out in various ways.

But the support personnel are another story: it's unlikely, especially in the early stages of charter growth, that the district can or will get rid of support personnel in a way that parallels enrollment losses as easily as it can shed instructional personnel. A principal, for example, is needed for every building: it isn't likely the district will close a building and get rid of a principal when it's only lost a few students in each building.

In this scenario, after enrollment losses to charter schools, instructional personnel (teachers) to students remains 25-to-1. But support staff to pupil goes from 500-to-1 to 475-to-1. This is an increase in spending per pupil: fewer pupils per staff member will raise the cost per pupil of that staff member.

This is an example of what we'll call a fixed cost. Scholars of school finance have, in fact, noted this for decades: some spending in schools is easier to adjust than other spending when enrollment falls. The question I tried to ask in this report is: does the data reflect this trend?

Spending, Revenues, and Charter Growth

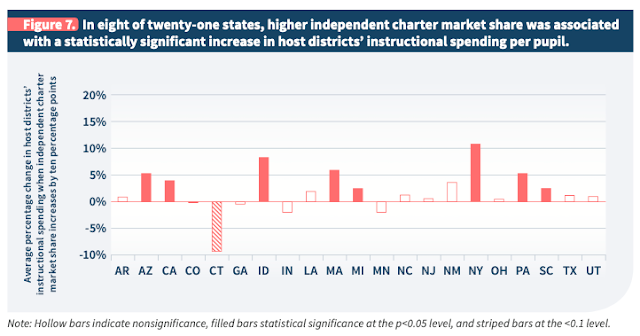

It turns out that, in many states, we see what I'm showing above. Here's the graph from the report showing how charter growth correlates with instructional spending:

And here's the graph for support spending:

The correlation for support spending is significant in many more states than instructional spending; further, the effect measured is larger for support than for instruction spending. I believe this is fairly solid evidence that there are differences in the ways different types of spending respond to charter growth, something economists refer to as elasticity.

Now, an important question is why the spending is allowed to rise. Don't school districts have a limited amount of funds available to them? Wouldn't they just have to deal with the enrollment losses and fixed costs by adjusting their spending as best as they could?

Not necessarily. First, it could be that other areas of spending are being cut, possibly to the detriment of the district, that don't show up in the data. The spending I'm tracking is current spending, which excludes things like debt service and capital outlays. It could be that districts are holding off on facilities spending, or other types of spending not included in my dataset.*

But there's another possibility: that more per pupil revenue is actually being put into the system to help address those fixed costs. It could, in fact, be the same amount of revenue but spread out over fewer students.

My analysis shows evidence that's happening -- but the type of revenue, like the type of spending, seems to differ. School districts get revenues from three main sources: the federal government, the state, and localities. Federal revenues average less than 10 percent of the total, although that varies from district to district. The rest is some combination of state and local revenues.

The report shows a significant difference in how state and local revenues correlate with charter growth. Here, for example, is the correlation between charter share and state revenues:

And here it is with local revenues:

In many states, local revenue increases correlate more significantly with charter school growth. Why would that be? Part of the reason may be that, in states where charter schools receive funding directly from the state, local revenues don't decline when students leave local districts. The local school taxes, in other words, don't necessarily go down as enrollment declines. The same amount of revenue spread out over fewer students will lead to higher revenues per pupil. But if that same state is giving state funding based on a per pupil formula, per pupil revenues from the state won't increase.

Now, a charter supporter may look at this and say: "Great! In many states, there's no fiscal harm to local districts as charters come in! This proves charter schools don't harm district budgets!"

Not so fast...

Cost vs. Spending

One of the worst errors people make in trying to understand school finance is conflating cost with spending. Spending is easy to understand: it's simply the monies you put out toward educating students. OK, it can get a bit more complicated, especially when trying to categorize different types of spending... but it's important to understand that spending is not cost.

Cost is the amount of spending you need to get a student to meet a particular educational outcome: a test score, a graduation rate, etc. You'll often hear critics of public schools bemoan what they say are the out-of-control spending amounts in public versus private schools, claiming this proves public schools are wasting money. What they don't understand (or do, but won't admit) is that different schools with different contexts having different students have different costs.

A school that is located in a more competitive labor market has higher costs. So does a school enrolling more children with a special education need, or who don't speak English at home, or is located in an area with a higher concentration of poverty. Getting to a place where these children have equal educational opportunity requires more resources and, therefore, indicates a higher cost.

Charter school supporters will often point out that charters educate their students at a lower level of per pupil spending than district schools. But that misses the point: charters often have a lower per pupil cost. Charters enroll fewer students with costly special education needs than district schools. In many jurisdictions, charters enroll smaller proportions of English language learners, or students in economic disadvantage. In these cases, their cost is less than a school district's; simply comparing per pupil spending figures misses this critical point.

It also ignores the fact that most school districts have distinctly different responsibilities than their charter school neighbors. Public school districts have to be ready to find a seat for any child who comes into their boundaries at any time of year. They have to enroll students in all grade levels, and not just the ones they choose to offer. They have to offer curricular choices and extracurriculars to their students that those in charters may elect to forego when enrolling. And in many cases, school districts have to provide services for both district and charter students, such as transportation.

So it may be that districts need additional monies because their costs are higher. But it's also true that spending isn't always going to improve an educational outcome. It could be that more money put into a school doesn't increase student learning or opportunity: that spending would be inefficient. The term often carries a pejorative sense with it, as if anything inefficient can simply be addressed by better choices. But sometimes those choices aren't clear, and sometimes we expect greater efficiency from those who haven't had the power to make those choices -- like whether charter schools should proliferate.

It is, to my mind, very likely that the additional spending that accompanies charter growth is inefficient, because that additional spending is mostly for fixed costs. For that reason, it is also very likely that school districts can't improve their practices to make themselves more efficient; in other words, so that their additional spending could improve student outcomes. It may well be that the increased per pupil spending simply reflects the reality that districts need to do the same job as always, but for fewer students. For this reason, it's impractical to ask a district to perfectly reduce its administrative, support, and facilities spending in alignment with their enrollment losses to charters.

So, no, this report is not a finding that charters don't harm school district finances; neither is it a finding that they do. It is, instead, a description of what seems to be happening to school districts as charters come in -- although that description comes with many caveats attached...

Limitations

I'll be doing a wonky post about the problems with modeling spending and revenue changes when charters grow at some point in the next few weeks. But I want to address some questions I've received about the limitations on this study.

- A note on my analysis: what I'm using is known as a fixed-effects model. The basic idea is that every school district has unique characteristics, and we should account for those characteristics when estimating the effects of charter growth on district finances. We also need to account for changes that affect all districts year-to-year. A fixed-effects model allows for that, and for other varying factors that may also affect spending, such as different student populations, density, labor market effects, etc.

But a fixed-effects model cannot say with certainty that changes in charter growth caused the correlated changes in financial measures. It could be that there are other factors involved that account for the changes -- we just don't know. That said, the estimates in the report provide enough evidence that the relationship may exist that it's worth investigating further.

- My measure of charter school penetration assumes that all students in a charter school would otherwise attend public school in the district where the charters is located. There is no federal data available that directly ties a charter school student to their "home" district, so this is really the best I can do with the given data.

We know, however, that charter school students can and do cross school district boundaries, so the percentages of charter penetration are not exact. There are also quirks in some state's charter regulations (California is a good example) where distant districts can authorize charters, making the figures even more imprecise.

That said, there is previous research that uses the same methods I do and compares it to actual district-level data that gives precise measures of charter penetration. That research generally shows the measures lead to similar estimates. So, yes, I'm using a proxy measure -- but there's reason to believe it's a pretty good proxy,.

- There is one aspect to this last point that requires more caution when approaching the estimates: virtual charter schools. While the overall percentage of students in these schools is low, there is more penetration in some states and districts than others. Tying virtual charter enrollments to district boundaries is obviously not going to work, and that will bias the estimates, although it's impossible to say how much.

I did some work to try to mitigate against this, and continue to work to solve the problem. The biggest issue is the data, which is not very good. That said, I should have been more clear in the report about this issue -- and that's entirely on me.

- One of the biggest issues we came across is dealing with the problem of scale. We could, for example, ask this as the research question: "How do charter schools affect district finances not including the effects of enrollment losses?" That would allow us to control for those losses in the model... but what if we think (as I do) that enrollment losses are the primary mechanism through which charters change district finances? If we included a scale measure in the model, it would "eat up" the charter effect, because detangling charter effects and enrollment losses is impossible.

The problem is further complicated because other scale effects unrelated to charter growth are very likely impacting district finances. So we have to account for scale, but not scale changes due to charters. This was tricky, and, as the appendix on this in the report suggests, the solution is definitely up for debate. I'll discuss this more in the next post.

Let me just add this: if anyone thinks one report using one method and one set of data by one guy settles any question of public policy... then you really don't understand how social science works. Which brings me to...

My Takeaways On All This

As I've said on this blog and elsewhere many times: I am not for abolishing charter schools. I started my K-12 teaching career in a charter, run by good people who were committed to their students and their school. I have seen repeatedly in my teaching career that some students are not well suited to the "typical" public district school, and would benefit from an alternative that better suits their needs. I have no problem with charters being proud of their students and their schools, and I have never and would never criticize a parent for making the choice to enroll their child in a charter.

What I am against are the facile, often lazy, and sometimes outright mendacious arguments made in favor of charter schools by some -- some -- of their most ardent supporters.

There is no question that there are

bad actors in the charter sector, and that they have caused unnecessary

waste, fraud, and abuse against the taxpayers and families they are supposed to serve. There is no question that the current charter authorization and oversight system is completely inadequate to the task and

needs to be reformed; consequently, many charters act in ways that are not in the

best interest of citizens.

I am also deeply concerned that charters, particularly of the "no excuses" variety, are imposing a type of education on students of color that would

never be tolerated by white parents in affluent school districts. The stories of students being denigrated and subject to carceral educational practices are

well-known and

far too common.

Some argue the gains these schools show are worth it. I first want to point out that the overall effect of charters on student outcomes has been little to nothing; at best, the positive effects are confined to "no excuses" urban charters. The peer-reviewed literature on charter schools of this type often shows a positive effect; what usually gets missed, however, is why those effects occur. I've seen no evidence that these charters have pedagogical or organizational advantages that lead to better student outcomes. What seems to be happening instead is that certain self-selected students benefit from longer days, longer years, and one-on-one tutoring.

These things cost money, which begs a question: If we can find additional funds for some students in charters to have more resources, why can't we find it for all students, including those in public schools?

My point in reiterating all this is that the debate about charter schools has to move to a new level; the old tropes weren't accurate and we have to get past them. So I have little patience at this point with those in the pro-charter camp who dismiss the many, many problems charter schools are creating for public education. And no, I don't think there is equivalent bad-faith argument on "both sides."

But neither do I think the charter-skeptics, of which I count myself, have had the issue of charter school growth's effect on district finances completely right. There are mechanisms and compensatory policies that, in many states, appear to increase per pupil spending and revenues at school districts as charters move in. This doesn't mean that districts don't suffer fiscal harm; rather, the simple story of "charters taking money away from districts" is more subtle and complex than what some have understood.

One last, completely self-indulgent thought: the more I do this kind of work, the more humble I've become about it. It is far too easy to screw up a dataset, or make a mistake when coding a model, or make a conceptual error, or overlook some critical factor. I tend to get obsessive about triple checking things, but my biggest fear remains putting something out that is just flat out wrong.

Yes, some research is more rigorous than others. Sometimes people come to conclusions their analysis doesn't warrant. Some people are clearly hacks. But if you're transparent, and you're open about your limitations, and you're willing to have a good faith discussion about your findings, I'm not going to fault you, no matter what you believe or what you find. Because I know this stuff isn't easy.

I didn't always take that view; I try to now. More to come.

* I did do some modeling on this, but I grew suspicious of the data, as it's not clear states report capital spending consistently. More later.