The usual end-of-year school rites for our fifth-grader are especially bittersweet this year, because it is her last at the charter school where she has learned, played, made friends and grown since kindergarten.Unlike many kids at her stage, she had a choice to stay at her K-8 school — but as a family we together decided to jump from the charter to a district junior high run by the city’s Department of Education.Some extracurricular forces eased the choice. My husband, who’s logged hundreds of miles driving to and fro, will hand our girl off to a convenient bus. She in turn will be thrilled to shed a loathed uniform. Me, I look forward to an end to lunch box prep, thanks to an improved cafeteria menu.But the bottom line is that her elementary-school years were marked with a whirlwind of teachers that, if she and her classmates were lucky, would last the year and then move on.

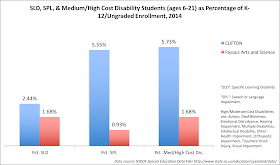

What Katz describes here is quite typical for charters around the nation. In my report on New Jersey charter schools' finances and staffing, I found clear distinctions between charter and public district educators: charter teachers have less experience, are less likely to have an advanced degree, and are paid less, even when accounting for experience.The ritual became as certain as winter succeeded fall: Some parent would post on the school Facebook group that their child’s teacher was leaving mid-year. Moans and commiseration ensued.Our child avoided that fate until last fall, when, two weeks in, her promising teacher — a veteran at three years served — suddenly vanished, and a substitute arrived much sooner than any explanation. Her class rebound its footing, eventually, with a new teacher — but never quite recovered from those lost weeks. [emphasis mine]

There are exceptions. As I've noted before, the largest NJ charter networks, such as TEAM-KIPP and Uncommon (North Star), pay teachers more at the outset of their careers. But the lack of experienced teachers on the staffs of these charter networks suggests they don't hang around long enough to make the high-five figure salaries* district teachers start to make around their second decade in the profession.

The response I've had to this from charter cheerleaders, such as Peter Cunningham -- here writing in the News in reply to Katz -- is usually: "So what?"

I'll interrupt here to note that if unionized teachers are unhappy and leave the profession, there's little evidence it's because of unions themselves; "reform" and a lack of funding appear to play a much larger role in teacher dissatisfaction. Also, there is no evidence I am aware of that shows a negative correlation between school performance and unionization; research suggests quite the opposite, in fact.Daily News editorial writer Alyssa Katz has decided to pull her daughter out of a public charter school in New York City because of high teacher turnover. Katz cites a statistic that teacher turnover in the city's charters is more than twice as high as in unionized district schools, which generally pay more, have shorter hours and, of course, provide tenure protections and other benefits.To her credit, Katz acknowledges that New York's largest charter school organization, Success Academy, has "skyrocketing" test scores despite high rates of teacher turnover, which raises the question of whether teacher turnover is good or bad.The more important question is, however, should we even pay attention to teacher turnover?In theory, unions produce happier, more secure teachers and they, in turn, produce better educational outcomes. In practice, that's not the case. Lots of unionized teachers are very unhappy, enormous numbers of unionized teachers leave the profession, and lots of unionized schools get awful results.

Cunningham continues:

Fine, let's talk about results:Too often, in the ongoing education debates, charter opponents will talk about anything except results. They will harp on "no excuses" discipline practices. They will attack charter funders. They will complain about public charters draining funds from public schools.They won't talk about test scores, unless, of course, the scores are bad, in which case they will cite them and call for closing down low-performing charters. [emphasis mine]

In the aggregate and across the nation, there is little evidence charter schools get, on average, significantly better results than public district schools.

For example, the CREDO studies, long cited by charter advocates, show on average that the gains of the charter sector are, at best, quite small (even if CREDO oversells them by using a conversion to "days of learning" that is wholly invalidated).

There are pockets, however, such as Boston, where charter gains are larger. To be clear: the gains almost never come close to "closing the achievement gap," no matter how some in the credulous press choose to spin the results. But there are gains. The problem is that too many reformy folks want to end the conversation right there; what they should be asking is:

1) Why?

2) At what cost?

Over the past several years, it's become clear to me what the answers to #1 are:

- Student attrition (such as that found at Cunningham's beloved Success Academy, the Uncommon charters, and the vaunted Boston charter sector), often exacerbated by "no excuses" disciplinary policies,

- Unequal student populations, which likely create positive peer effects,

- Unobserved student differences that can only be controlled for crudely in the data we have,

- Self-selection, which not even the "lottery studies" can control for when generalized to the entire student population,

- Resource differences, sometimes due to philanthropy, sometimes due to unequal student populations,

- And...

A longer school day and school year, smaller class sizes, and one-on-one student tutoring.

This is the resource-intensive part of "no excuses" chartering that seems to always get lost in the conversation. Well, more accurately: it's never fully explored. Because everyone loves the idea of more teachers working a longer day and year for at-risk kids -- but they don't really like talking about the cost.

Basic economic theory suggests that getting people of equal qualifications and effectiveness to work a longer day and year will cost an employer more in wages. So charter schools have two choices for getting more teachers to work longer: they can pay more, or they can recruit less expensive staffs.

We've already noted that some large charter networks (and even some smaller ones) rely on their ability to gather philanthropic contributions to supplement the public funds collected so they can increase staff hours/days, and reduce student-to-teacher ratios. But the other way they can gain a resource advantage is to maintain a less expensive staff by constantly churning it. There is, however, a problem...

Teachers, like so many other professions, gain increases in wages through accumulated experience. A teacher who has 20 years of experience in the same district will almost always make more than one with only 10. Some have made the case experience and salary should be decoupled, but there's more chance of my winning the next Olympic silver medal in the backstroke than of that happening. We'd have to either cut experienced teacher wages and distribute them to inexperienced teachers, or pour a lot more money into the system; neither is going to happen in this world.

When teachers enter the profession, they are well aware of how the step guides work. Which means they are already acclimated to the idea that they will make considerably less in their earlier years with the reward of better pay later on.

As a teacher, I can also add that my personal experience with younger teachers is that they expect their first few years are going to be much rougher -- in terms of their time commitments, their stress levels, their choice of assignment, etc. -- than what will follow later in their careers.

Which brings us back to the critical section of Katz's piece:

The big reason for charters’ turnover plague is plain as day: District school teachers are universally represented by teachers unions, and enjoy contracts whose ample benefits include generous pension plans, non-negotiable business hours and tenure.

When our child’s teacher got an offer on Long Island last September, that was that.

Charter school teachers, in glaring contrast are often called on to work extra hours after school, and during summers, and whenever.

Which job would you pick if given a choice? Not even a close call. For all but the Teach for America types who intend to log a few years and switch tracks, the union jobs are better jobs, where educators build careers.The data we have on charter teacher attrition is pretty thin, but we do know a few things. The teacher attrition rate at high-profile carter networks like Success Academy is very high compared to the NYC public schools, and switching between schools within the network doesn't account for the disparity. Charter teachers do often cite working conditions and job dissatisfaction as reasons for leaving their schools. Chris Torres finds that when a teacher perceives that their workload is too great at a charter, that teacher is more likely to leave (although there appears to be an interaction with teachers' perceptions of their schools' leadership).

We need better empirical evidence to back up a claim that charter schools are serving as springboards for teachers in search of unionized jobs in public district schools. But the anecdotal evidence is certainly piling up:

One veteran charter school teacher who requested anonymity, wary of her school’s response to her comments, says that even as schools use teachers, teachers use schools—as way stations to other, long-term goals. Often, she said, new teachers work for a year or two at a charter school to buff up a resume, ahead of a search for a union job. “People go there [to charters] until they can get another job. It’s a stepping stone to a teaching career, to a union job with benefits, like vacation, and tenure.” [emphasis mine]There is, in my opinion, at least enough evidence so far to suggest this is a plausible theory. Which brings us to the problem of "free riding." Martin Carnoy explains:

The “free rider” aspect of teacher costs in private schools, whether voucher or charter, means that the supply of young people entering the teaching profession is maintained by the salary structure and tenure system in public education. Without this structure, many fewer individuals would take the training needed to become certified to enter teaching. Since teaching salaries are low compared with other professions, the prospect of tenure and a decent pension provides the option of security as compensation for low pay. This pool of young, trained teachers is available to voucher and charter schools, generally at even lower pay than in the public sector and without promise of tenure or a pension, but with the possibility of training and experience. Thus, the public education employment and salary system “subsidizes” lower teacher costs in private and charter schools. In other words, for private schools to have lower costs, it is necessary to maintain a largely public system that pays teachers reasonable (but still low) salaries and provides for a teacher promotion ladder and job security. [emphasis mine]It's telling to me that Katz's teacher took a job on Long Island. The ultimate goal wasn't just a public school job; it was a job at a particular type of public school.** We know that teachers in urban schools, in schools with greater proportions of economically disadvantaged students, and in schools with worse academic performance are more likely to move to a new school.

What is likely happening now is that the pattern of teachers leaving urban schools for what they perceive as less stressful jobs is being amplified by the larger work demands and smaller pay of charter schools.

Urban public school teachers might have been more likely to move to another district before, but at least their school days and years were similar to more affluent districts. Charter teachers, however, don't even have that in common: they get even lower pay and even longer hours.

Urban teachers might also have stayed in their districts because they earned tenure, which they'd have to give up when changing districts. Charter teachers often never gain tenure. So why would they ever stay if a better paying, less stressful, more secure gig comes along?

What Cunningham, with his focus on "results," fails to see is that the problem here is bigger than we'd think by simply looking at some -- some -- charters' somewhat better test scores. First, there's good reason to believe a model like this can't be sustained as charter proliferation grows.

Second: The charter school model depends on public schools subsidizing the free riding of charters. If that free riding isn't accounted for in resource distribution, the charters are creating patterns of inequity.

Charter cheerleaders often talk about what "high-performing" charters can teach public district schools. I'd argue that if "high-performing" charters are teaching us anything that can be applied to the entire system, it's that resources smatter. Charters may get those extra resources through things like philanthropy -- or they may artificially gain a resource advantage through churning an inexperienced staff that is ultimately subsidized through the public, district schools.

In either case, it's an unfair advantage, and it needs to be acknowledged before anyone makes the case that charters "do more with less." Increasingly, the evidence suggests the few charters that "do more" are doing so because they have more.

* Re-reading that sentence heightens its absurdity: "Ooh, high-five figures! In New Jersey! For college-educated professionals! After 15-20 years! What a deal!"

The teacher pay penalty is real and it cuts across the entire profession, not just the charters. But as poorly paid as teachers may be, charter teachers are paid even worse.

** OK, school districts on Long Island do vary considerably in their resources and their student populations. We don't know exactly where Katz's child's teacher wound up.